Sampling time-limited signals

The sampling theorem is a fundamental principle in signal processing that is used in various technologies, including digital communication and digital audio processing. In short, this theorem states that a bandlimited signal, i.e. a signal whose Fourier Transform is zero above a certain frequency, can be perfectly reconstructed if sampled higher than twice its highest frequency component. By sampling the signal with this rate, the resulting discrete-time signal has a spectrum consisting of multiple copies of the original bandlimited spectrum, each centered at an integer multiple of the sampling frequency. To recover the original analog signal, we can apply a low-pass filter that keeps a single copy of the spectrum centered around the origin.

Despite its seemingly straightforward statement, the theorem involves several subtleties that are not immediately apparent. For one, the theorem assumes that the signal is bandlimited. However, there is a fundamental theorem in Fourier Analysis, known as the “uncertainty principle,” which states that a signal cannot be limited both in the frequency and time domain at the same time1. Therefore, the sampling theorem only holds when our signal has (non-zero) values from \(-\infty\) to \(+\infty\). However, in practice, signals are limited in time. For instance, a song we wish to sample and later reconstruct has a finite duration (let’s say 4 minutes). Hence, this signal would have an infinite bandwidth in the frequency domain.

Considering this, how can sampling be performed for finite-duration signals, which are the only type that appear in practice?

To perfectly sample and reconstruct a time-limited signal, we must use an ideal anti-aliasing filter before sampling. This filter ideally cuts off all content of the signal above a certain frequency, ensuring that our signal is (ideally fully) bandlimited. With a bandlimited signal, sampling does not cause any overlaps between frequencies of the signal (to review what ‘overlap’ means here, I suggest reviewing the sampling theorem from the references provided at the end of the article).

We may now ask: Since an anti-aliasing filter removes the frequencies of the signal above a certain value, how different is the output of the filter compared to the original signal? In other words, if we send our signal through an anti-aliasing filter, then take an inverse Fourier Transform to retrieve the time-domain signal, does the output resemble the orignal signal?

To answer this, first let’s compare the energy of the original and the filtered signal. An anti-aliasing filter affects the signal based on how much of the signal’s energy was beyond the cutoff frequency of the filter (recap Parseval’s theorem). In particular, a signal may have the majority of its energy below a certain frequency, with negligible content beyond that threshold. For such signals, the anti-aliasing filter does not significantly alter the energy of the original signal (however, it extends the signal from \(-\infty\) to \(+\infty\)). To illustrate what was mentioned above, assume we have an audio signal consisting of a single sine wave, let’s say at 400 Hz. Mathematically, such a signal is a truncated sine wave. The spectrum of a sine wave consists of two delta functions located at positive and negative frequencies. Truncating a sine wave is equivalent to multiplying the sine wave by a rectangular function defined as:

\[x(t) = rect(\frac{t}{\tau}) \sin{\omega_c ft}\]Where,

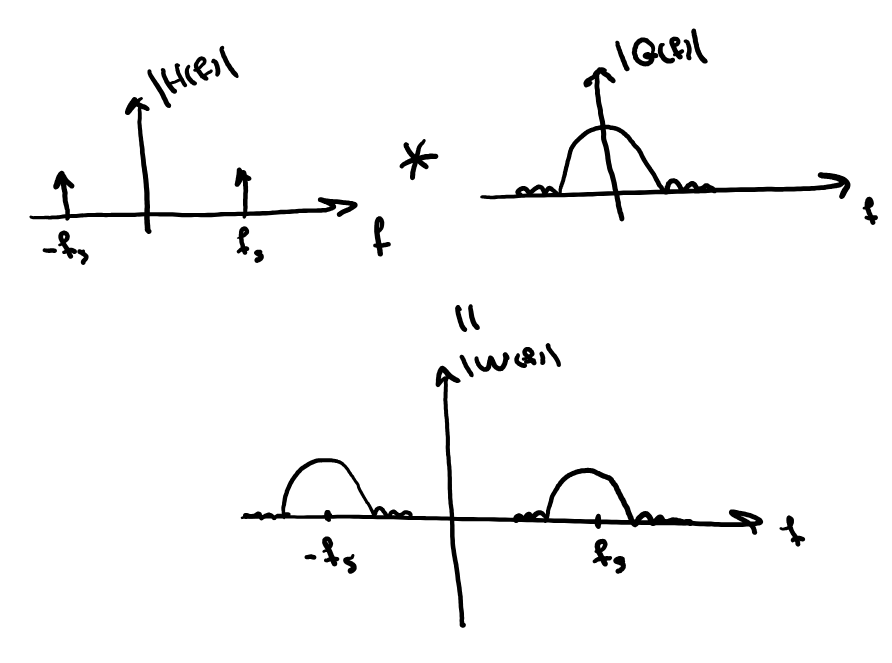

\[\operatorname{rect(\frac{t}{\tau})} = \begin{cases} 1, & |t| \leq \frac{\tau}{2} \\ 0, & |t| > \frac{\tau}{2} \end{cases}\]A key theorem in Fourier analysis states that multiplying two functions in the time domain corresponds to convolving their Fourier transforms in the frequency domain, and vice versa. Putting everything together, the spectrum of a truncated sine wave is computed as the convolution of two Dirac pulses (corresponding to the sine wave) and the sinc function (corresponding to the rectangular function).

As it can be seen in the graph, the majority of the spectrum of a the truncated sine is around the first lobe of the sinc function located at \(+f_s\) and \(-f_s\). In signals & systems terms, we refer to the bandwidth that contains the majority of the energy of the signal as the essential bandwidth. Mathematically, it can also be proven that the essential bandwidth of a rectangular singal is \(1/\tau\). Consequently, the longer truncated sine wave, the narrower the effective bandwidth. As a result, when the sine wave is sufficiently long, an anti-aliasing filter will remove only an insignificant amount of energy from the signal.

As a side note, the spilling of frequency content—corresponding to the sine wave onto adjacent frequencies is known as spectral leakage. This concept appears in various areas of digital signal processing (DSP). An example is the design of FIR filters using the windowing method (P.S. You can design and experiment with such filters using the web app I developed a while ago at dsptoolkit.github.io).

Back to the truncated sine signal, we compared the original signal and the filtered signal in terms of their energy. But how about the shape of the orignal and the filtered signal? To answer this, we again use the property of the Fourier transform that states that convolution and multiplication in the frequency and time domains are duals of each other. Specifically, when an ideal anti-aliasing filter is applied to the signal in the frequency domain, that is equivalent to the convolution of a sinc pulse with the original signal in the time domain. How would that change the signal? Well, we have to do the convolution to answer that. However, something we can guarantee is that it will be a signal whose majority of energy is concentrated in a finite interval of time. How can we prove that? As we have already seen, the essential bandwidth of a sinc pulse is limited and equals the first lobe of the signal. Subsequently, when we convolve such a signal with a time-limited signal, we get something that its energy is concentrated in a finite interval as well.

Lastly, we can ask: How does the sampling theorem apply to a signal with a short duration? That is, we have a signal that is multiplied by a short rect function. To achieve this, we can sample the signal at a rate much higher than twice the frequency of the sine wave. This ensures that the majority of the signal’s energy remains below the cutoff frequency of the anti-aliasing filter.

Final remarks

In this post, we assumed that the anti-aliasing filter was an ideal low-pass filter that removes all frequencies beyond a certain value. However, such filters are non-causal. Though mathematically correct, it is not possible to build a physical device that could operate in real time. This is because a non-causal filter requires knowledge of future values of the signal, and that information is not available in real-time applications. In practice, real anti-aliasing filters pass frequencies below the cutoff frequency, and significantly reducing the ones above it. This suppresses the higher frequencies but does not eliminate them entirely. In other words, a practical anti-aliasing filter does have an infinite bandwidth. As a result, some spectral overlap inevitably occurs during sampling. However, this overlap is so minimal that it does not meaningfully affect the signal’s spectrum.

References

[1] Oppenheim, Alan V., Alan S. Willsky, and Syed Hamid Nawab. Signals & systems. Pearson Educación, 1997.

[2] Lathi, Bhagwandas Pannalal, and Zhi Ding. Modern digital and analog communication systems. Vol. 3. New York: Oxford university press, 1998.

-

As an example, the Fourier Transform of a rectangular function in time (which is a time-limited signal) is the sinc function in frequency, which has values for all frequencies from \(-\infty\) to \(+\infty\). ↩